Rock Strongo

dodgy Dave Goosegog

@dawaxman I get your point. And here's a piece I found to be a good read. (I bolded out the parts most relevant regarding family victims.)

A Critic at Large JANUARY 25, 2016 ISSUE

Dead Certainty

How “Making a Murderer” goes wrong.

BY KATHRYN SCHULZ

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A private investigative project, bound by no rules of procedure, is answerable only to ratings and the ethics of its makers.CREDITILLUSTRATION BY SIMON PRADES

Argosy began in 1882 as a magazine for children and ceased publication ninety-six years later as soft-core porn for men, but for ten years in between it was the home of a true-crime column by Erle Stanley Gardner, the man who gave the world Perry Mason. In eighty-two novels, six films, and nearly three hundred television episodes, Mason, a criminal-defense lawyer, took on seemingly guilty clients and proved their innocence. In the magazine, Gardner, who had practiced law before turning to writing, attempted to do something similar—except that there his “clients” were real people, already convicted and behind bars. All of them met the same criteria: they were impoverished, they insisted that they were blameless, they were serving life sentences for serious crimes, and they had exhausted their legal options. Gardner called his column “The Court of Last Resort.”

To help investigate his cases, Gardner assembled a committee of crime experts, including a private detective, a handwriting analyst, a former prison warden, and a homicide specialist with degrees in both medicine and law. They examined dozens of cases between September of 1948 and October of 1958, ranging from an African-American sentenced to die for killing a Virginia police officer after a car chase—even though he didn’t know how to drive—to a nine-fingered convict serving time for the strangling death of a victim whose neck bore ten finger marks.

The man who didn’t know how to drive was exonerated, at least partly thanks to coverage in “The Court of Last Resort,” as were many others. Meanwhile, the never terribly successful Argosy also got a reprieve. “No one in the publishing field had ever considered the remote possibility that the general reading public could ever be so interested in justice,” Gardner wrote in 1951. “Argosy’s circulation began to skyrocket.” Six years later, the column was picked up by NBC and turned into a twenty-six-episode TV series.

Although it subsequently faded from memory, “The Court of Last Resort” stands as the progenitor of one of today’s most popular true-crime subgenres, in which reporters, dissatisfied with the outcome of a criminal case, conduct their own extrajudicial investigations. Until recently, the standout representatives of this form were “The Thin Blue Line,” a 1988 Errol Morris documentary about Randall Dale Adams, who was sentenced to death for the 1976 murder of a police officer; “Paradise Lost,” a series of documentaries by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky about three teen-agers found guilty of murdering three second-grade boys in West Memphis in 1993; and “The Staircase,” a television miniseries by Jean-Xavier de Lestrade about the novelist Michael Peterson, found guilty of murdering his wife in 2001. Peterson has been granted a new trial. Randall Dale Adams was exonerated a year after “The Thin Blue Line” was released. Shortly before the final “Paradise Lost” documentary was completed, in 2011, all three of its subjects were freed from prison on the basis of DNA evidence.

In the past fifteen months, this canon has grown considerably in both content and prestige. First came “Serial,” co-created by Sarah Koenig and Julie Snyder, which revisited the case of Adnan Syed, convicted for the 1999 murder of his high-school classmate and former girlfriend, eighteen-year-old Hae Min Lee. That was followed by Andrew Jarecki’s “The Jinx,” a six-part HBO documentary that, uncharacteristically for the genre, sought to implicate rather than exonerate its subject, Robert Durst. A New York real-estate heir, Durst was acquitted in one murder case, is currently awaiting trial in another, and has long been suspected in the 1982 disappearance of his wife, Kathleen Durst.

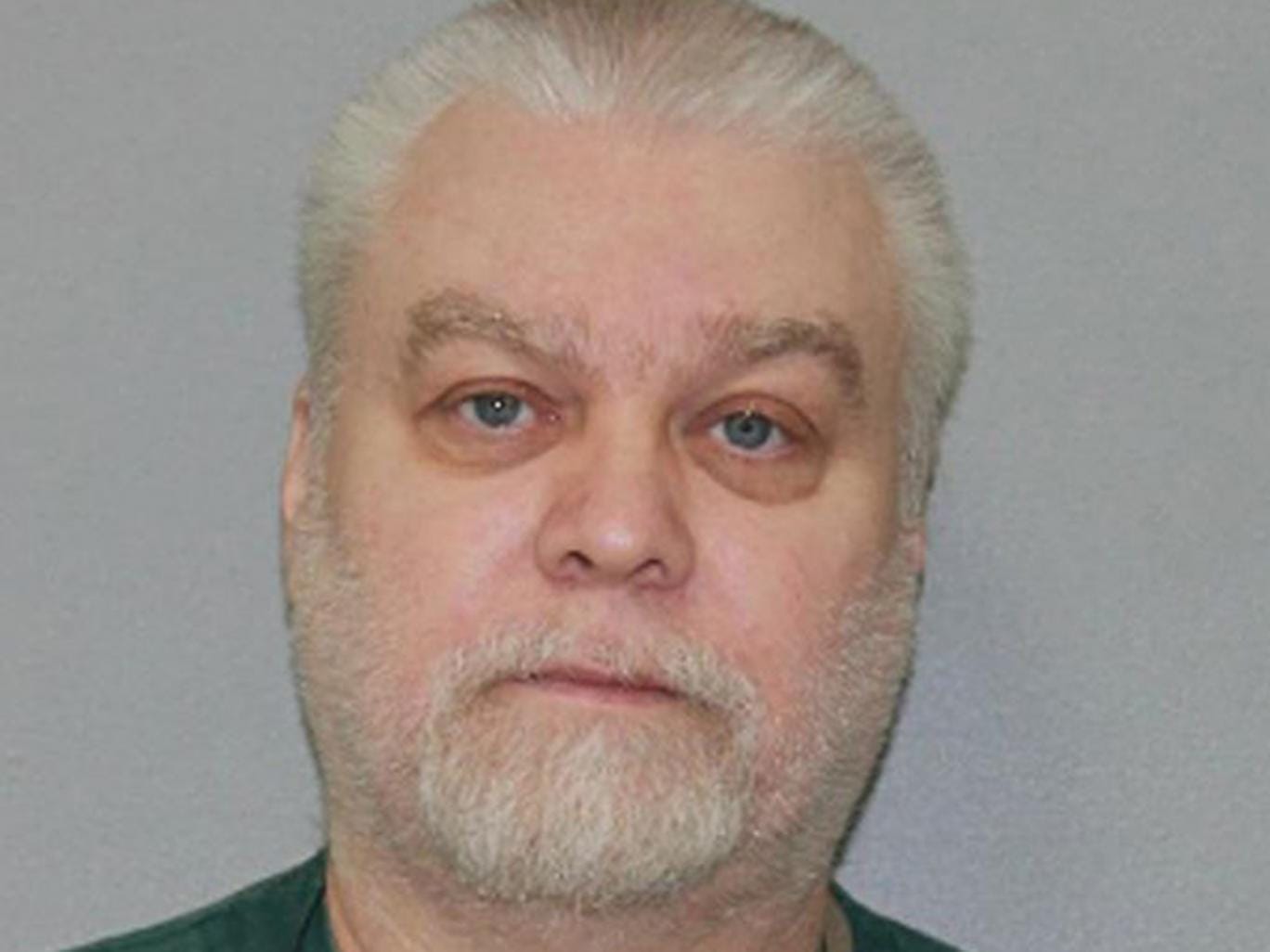

The latest addition to this canon is Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos’s “Making a Murderer,” a ten-episode Netflix documentary that examines the 2007 conviction of a Wisconsin man named Steven Avery. Like the prisoners featured in “The Court of Last Resort,” Avery is a poor man serving time for a violent crime that he insists he didn’t commit. The questions his story raises, however, are not just about his own guilt and innocence. Nearly seventy years have passed since Erle Stanley Gardner first tried a criminal case before the jury of the general public. Yet we still have not thought seriously about what it means when a private investigative project—bound by no rules of procedure, answerable to nothing but ratings, shaped only by the ethics and aptitude of its makers—comes to serve as our court of last resort.

A Critic at Large JANUARY 25, 2016 ISSUE

Dead Certainty

How “Making a Murderer” goes wrong.

BY KATHRYN SCHULZ

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A private investigative project, bound by no rules of procedure, is answerable only to ratings and the ethics of its makers.CREDITILLUSTRATION BY SIMON PRADES

Argosy began in 1882 as a magazine for children and ceased publication ninety-six years later as soft-core porn for men, but for ten years in between it was the home of a true-crime column by Erle Stanley Gardner, the man who gave the world Perry Mason. In eighty-two novels, six films, and nearly three hundred television episodes, Mason, a criminal-defense lawyer, took on seemingly guilty clients and proved their innocence. In the magazine, Gardner, who had practiced law before turning to writing, attempted to do something similar—except that there his “clients” were real people, already convicted and behind bars. All of them met the same criteria: they were impoverished, they insisted that they were blameless, they were serving life sentences for serious crimes, and they had exhausted their legal options. Gardner called his column “The Court of Last Resort.”

To help investigate his cases, Gardner assembled a committee of crime experts, including a private detective, a handwriting analyst, a former prison warden, and a homicide specialist with degrees in both medicine and law. They examined dozens of cases between September of 1948 and October of 1958, ranging from an African-American sentenced to die for killing a Virginia police officer after a car chase—even though he didn’t know how to drive—to a nine-fingered convict serving time for the strangling death of a victim whose neck bore ten finger marks.

The man who didn’t know how to drive was exonerated, at least partly thanks to coverage in “The Court of Last Resort,” as were many others. Meanwhile, the never terribly successful Argosy also got a reprieve. “No one in the publishing field had ever considered the remote possibility that the general reading public could ever be so interested in justice,” Gardner wrote in 1951. “Argosy’s circulation began to skyrocket.” Six years later, the column was picked up by NBC and turned into a twenty-six-episode TV series.

Although it subsequently faded from memory, “The Court of Last Resort” stands as the progenitor of one of today’s most popular true-crime subgenres, in which reporters, dissatisfied with the outcome of a criminal case, conduct their own extrajudicial investigations. Until recently, the standout representatives of this form were “The Thin Blue Line,” a 1988 Errol Morris documentary about Randall Dale Adams, who was sentenced to death for the 1976 murder of a police officer; “Paradise Lost,” a series of documentaries by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky about three teen-agers found guilty of murdering three second-grade boys in West Memphis in 1993; and “The Staircase,” a television miniseries by Jean-Xavier de Lestrade about the novelist Michael Peterson, found guilty of murdering his wife in 2001. Peterson has been granted a new trial. Randall Dale Adams was exonerated a year after “The Thin Blue Line” was released. Shortly before the final “Paradise Lost” documentary was completed, in 2011, all three of its subjects were freed from prison on the basis of DNA evidence.

In the past fifteen months, this canon has grown considerably in both content and prestige. First came “Serial,” co-created by Sarah Koenig and Julie Snyder, which revisited the case of Adnan Syed, convicted for the 1999 murder of his high-school classmate and former girlfriend, eighteen-year-old Hae Min Lee. That was followed by Andrew Jarecki’s “The Jinx,” a six-part HBO documentary that, uncharacteristically for the genre, sought to implicate rather than exonerate its subject, Robert Durst. A New York real-estate heir, Durst was acquitted in one murder case, is currently awaiting trial in another, and has long been suspected in the 1982 disappearance of his wife, Kathleen Durst.

The latest addition to this canon is Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos’s “Making a Murderer,” a ten-episode Netflix documentary that examines the 2007 conviction of a Wisconsin man named Steven Avery. Like the prisoners featured in “The Court of Last Resort,” Avery is a poor man serving time for a violent crime that he insists he didn’t commit. The questions his story raises, however, are not just about his own guilt and innocence. Nearly seventy years have passed since Erle Stanley Gardner first tried a criminal case before the jury of the general public. Yet we still have not thought seriously about what it means when a private investigative project—bound by no rules of procedure, answerable to nothing but ratings, shaped only by the ethics and aptitude of its makers—comes to serve as our court of last resort.